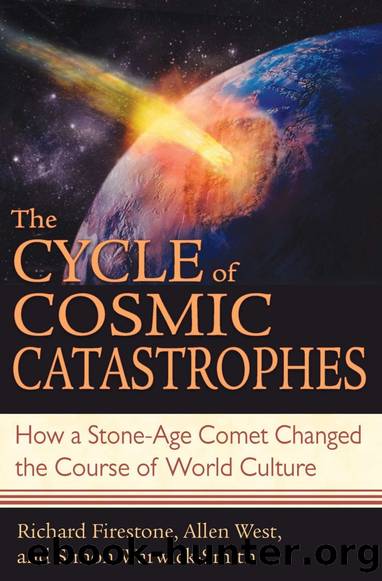

The Cycle of Cosmic Catastrophes: How a Stone-Age Comet Changed the Course of World Culture by Richard Firestone

Author:Richard Firestone [Firestone, Richard]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Published: 2010-02-16T15:54:43+00:00

1 9 4 THE EVIDENCE

Fig. 17.2. The âPrincess.â

Source: Library of Congress,

Edward S. Curtis Collection

That afternoon, the princess and other tribe members left the camp to see what had happened. They found that the explosions had burned giant holes into the ground and that rain-swollen streams cascaded into them.

The rains continued every day for thirteen moons, so that soon the craters were full. The giant hole closest to their camp became a huge fifteen-mile-long inland lake. They called it Mattamuskeet, the Lake on the Hill, and named their tribe after it.

Thanks to the falling stars, which brought much-needed water, they had survived. Out of seeming catastrophe came a new life.

R E T O L D F R O M BAREFOOT, 1995

PROBLEMS WITH THE IMPACT THEORY

Although the impact theory solves some major problems that the other theories cannot, it still must answer some remaining difficult questions. One of the main problems is with the dating. For the impact theory to be valid, we should find that all available bay dates are nearly the same, whether by radiocarbon or by a scientific dating method called optically stimulated luminescence, or O S L for short. T h a t is not the case, however. Although there are only a limited number of radiocarbon dates available for bays, the dates vary widely within a range of 4 8 , 0 0 0 to 6 , 0 0 0 years. O S L and radiocarbon dates on bay rims range from 1 0 8 , 0 0 0 to 2 , 0 0 0 years ago.

THE CAROLINA BAY CRATERS 1 9 5

So how can we explain that wide range? In summary, the bay impact theory proposes that tremendous impact explosions blew tons of material into the air and randomly jumbled together older and younger sediment in a geologic process called reworking, or redeposition, so that, for example, a 70,000-year-old leaf was left lying right next to a 17,000-year-old tree branch. Redeposition makes accurate carbon dating very difficult, since nothing is in its original position.

In his report in 1 9 5 3 on Singletary Lake, a Bladen County bay, Frey complains about âredeposition confusing the recordâ (pp. 2 9 0 - 9 1 ) . Second, he complains about the difficulty of dating the bays because âthere are quite a number of ⦠abrupt changes,â by which he means that there are lots of missing sections of sediment. Clearly, the bays he worked on, which are typical of other bays, presented major difficulties for dating. Because of that, Frey, who did more work on the bays than nearly any other scientist, considered bay radiocarbon dates unreliable.

The same is true for O S L dating, a process that allows researchers to approximate the last time that quartz sand was exposed to sunlight. This is an important method for determining the age of a sandy surface that might include, for example, a Clovis spear point with no datable charcoal. The method works well when sand is deposited in a

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Fairy Tales | Folklore |

| Mythology |

Circe by Madeline Miller(8146)

Confessions of an Ugly Stepsister by Gregory Maguire(7891)

A Court of Wings and Ruin by Sarah J. Maas(7853)

Burn for You (Slow Burn Book 1) by J.T. Geissinger(7095)

The Bird and the Sword by Amy Harmon(5381)

A Lesson in Thorns (Thornchapel Book 1) by Sierra Simone(5086)

Into the Drowning Deep by Mira Grant(4483)

Stolen (Alpha's Control Book 1) by Addison Cain(4190)

The Queen and the Cure (The Bird and the Sword Chronicles Book 2) by Amy Harmon(4187)

Mythology by Edith Hamilton(3768)

Pernicious Red (When The Wicked Play Book 1) by Natalie Bennett(3521)

Run Little Wolf (The Forest Pack Series Book 1) by G. Bailey(3513)

The Queen and the Cure by Amy Harmon(3338)

(Maiden Lane #5) Lord of Darkness by Elizabeth Hoyt(3101)

Lost Boy by Christina Henry(3021)

Mythos by Stephen Fry(2870)

The Fairy Queen (The Dark Queens Book 6) by Jovee Winters(2820)

Persephone by Kitty Thomas(2707)

Bunny by Mona Awad(2450)